A sitting magistrate’s review of the MPTS hearing suggests the defence strategy may have backfired, possibly laying the groundwork for further scrutiny.

By James Murray-Hodcroft | The Hodlines

Published: 14th July 2025

When Dr David Cartland stood before the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (MPTS), few expected a smooth outcome for the controversial Cornwall GP. But what surprised many observers was how sharply his own barrister’s words appeared to backfire; potentially, setting the stage for further scrutiny.

Over two weeks of hearings, Barrister Paul Diamond attempted to downplay Dr Cartland’s conduct, describing it as “pub talk online” and arguing that Twitter was simply a “nasty place” where harsh words shouldn’t be taken too seriously. But in defending his client, Diamond made a series of statements that some observers argue did more to support the General Medical Council’s (GMC) case than refute it.

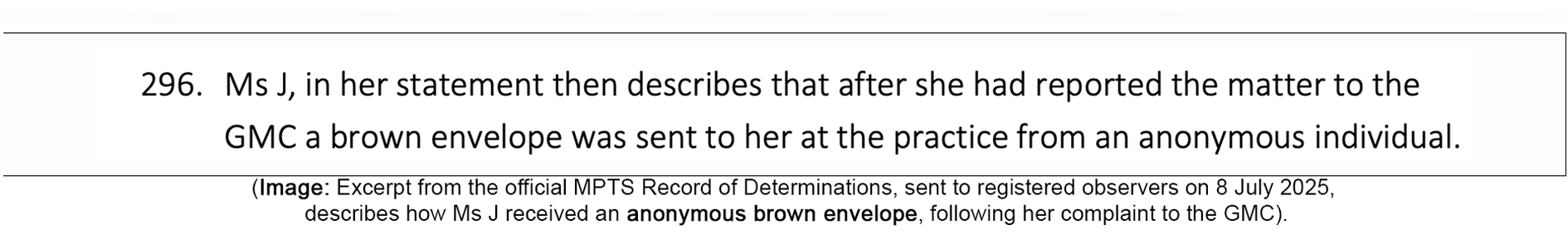

In one particularly striking moment, Mr Diamond argued that “some of the time the complainants would not have even known about the harassment,” citing the example of Ms A, who “only became aware after receiving an anonymous package in the post”.

While this may have been intended to downplay the awareness of harm, it inadvertently highlighted the real-world consequences of Dr Cartland’s online actions.

Under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, harassment does not require intent; it is sufficient that the conduct caused alarm or distress, and that the perpetrator knew or ought reasonably to have known it would. When Dr Cartland’s social media posts enabled others to identify Ms A and locate her place of work, the conduct arguably crossed that legal threshold.

Matters didn’t improve with further remarks. In an attempt to contextualize Cartland’s behaviour, Mr Diamond described him as “an emotional man. He doesn’t follow clear instruction. He loses it.”

A sitting magistrate, speaking anonymously due to judicial conduct restrictions, interpreted this as “almost a cry for help,” suggesting it painted a picture of a client difficult to manage. While clearly intended as mitigation, the impression left was of a doctor struggling with impulse control and professionalism.

Perhaps most contradictory was the argument that Dr Cartland had been left “in a bad place” by public criticism of his conduct, while simultaneously asserting that his own statements could not have harmed others. For some, this may have reinforced the view that Cartland was aware of the emotional impact such online commentary can carry and chose to ignore that risk, when directing it at others.

There was also rhetorical tension in the legal team’s appeal to Article 10 of the Human Rights Act (the right to freedom of expression). While this is a legitimate and important legal argument, some observers noted the irony, given that elements of the UK legal-political sphere where Diamond has appeared publicly have also advocated for the weakening or repeal of those very protections. Regardless, the argument failed to outweigh the tribunal’s overriding duty to uphold public confidence in the profession and ensure appropriate standards of conduct.

As an academic researcher focusing on online harassment and regulatory accountability, I’ve reviewed dozens of similar cases. Few, however, have featured a defence so internally contradictory. Shortly after the MPTS ruling, I spoke with the aforementioned magistrate (an expert in defamation/libel law) who described the defence as “potentially, quite damning” citing statements that “not only acknowledged damaging conduct but laid it out plainly on the record.”

That public record, now accessible to regulators, courts, or potential complainants, includes assertions that could be interpreted as prior admissions of awareness, emotional volatility, or disregard for professional responsibilities. If future claims arise, or if regulatory bodies reopen the matter, Mr Diamond’s courtroom commentary may well reappear; not in defence, but as supporting evidence for the other side.

In short: If Dr Cartland hoped this tribunal would close the book on the controversy, his defence may have just opened a new chapter.